Max is Not My Dad

You can receive future editions of the newsletter in your email by subscribing at: http://eepurl.com/j3EuP

***

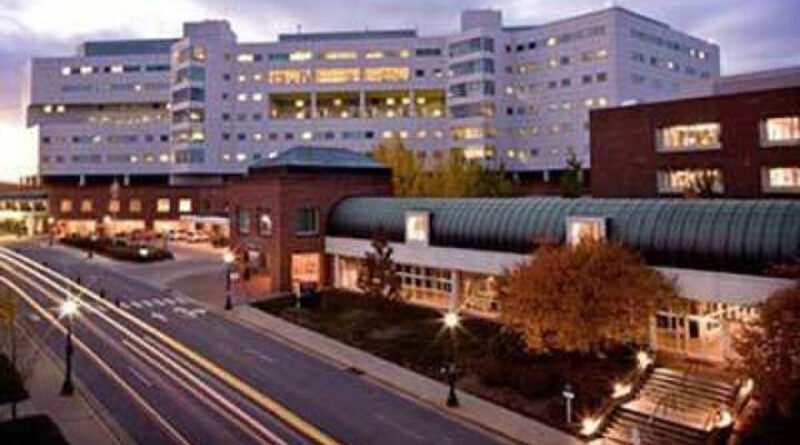

“Well I guess you’re a good son,” the lady on the phone says casually. I can hear her typing as she offers the pleasantry and I don’t bother to correct her. She’s probably got a hundred more phone calls to field that afternoon and she’s more likely looking for a way to fill the silence than making an honest assessment of me. Max and I are waiting in the parking garage out in front of the hospital because that’s the newest check-in protocol for his appointment. We must have followed four different protocols since January, but we’ll do what they ask so Max can get his biopsy. We’ve already made the 135-mile drive for the appointment, Max dozing in the backseat with both of us wearing masks the whole way. So, one phone call is hardly an inconvenience.

“Alright,” the lady says, bringing my attention back to the phone, “you can bring your father around to the front entrance and we’ll take it from there.” I thank her and put the car in drive. I won’t be able to go into the hospital with Max – another good protocol – so after I drop him off with a prayer, I’ll drive down the road a ways and park in a grocery store parking lot to wait. I’ve got a thermos of coffee, some emails to respond to, and an overflowing list of podcasts to listen to while I wait for Max to be done. I’ll pray too; I’ll pray that it’s just inflammation and not a return of Max’s cancer.

Max isn’t my dad, though he is the right age for it. He’s funny and introverted. He often prays that God will show him what God wants him to do, because Max nurses the thought that God has more for him to do in the world and he’s attentive for any sign of what that might be. His funniest stories are about his various stints in jail. But his most inspiring stories are about how God has moved since he got clean roughly five years ago. Max doesn’t drive, though sometimes he threatens to get his driver’s license again, but he doesn’t have much of a need for it since we’ll give him a ride where needs to go and he’s a bit of a homebody anyway. He offers hospitality in his home now that he’s sober and stable. Max, who once questioned if anyone could love him, is now a spiritual leader in our community and one of the quickest to remind people of his love for them. Max is so many things, but he isn’t my dad.

Because of our work and because of the community of which I am a part, people often mistake me for blood family of those with whom we share our lives. I’ve been called “son,” “brother,” and “husband” of lots of our folks both in person and on the phone. Most of the time I don’t correct people because it’s easier to keep the conversation moving than to clarify a point that doesn’t matter much. Whenever I’ve needed to clarify the point – say, at a hospital when one of our folks is very sick and doctors and nurses are looking for family – it has been a strange hiccup of a conversation as professionals try to figure out how to think of me and my relationship with my fellow community member. Often, folks like Max have offered some explanation that smooths past the confusion: “he’s my family, but not my blood.” There’s more than a little truth in those words.

My own father passed in August of 2019 and it is still hard when people mistakenly call me “son.” There’s a grieving part of me that wants to correct people, as if my dad’s memory is somehow lessened by the polite assumption of anonymous professionals. Of course, it isn’t, but part of me still flinches at the jarring thought. In those moments, I’m comforted by two thoughts. First, my father was proud of me – and, I believe, is still proud – and encouraged me to continue in this work, even once noting that we had quite the extended family in Danville. Second, in the days after my dad’s death, Max was praying for me and was eager to tell me he loved me. He and my father had met only occasionally, but Max found a way to distill a few good memories of my dad to share with me over the phone as I struggled to find words for my father’s funeral. It meant more than I can say.

On the 135-mile ride home, Max and I took turns telling stories and reminiscing. Storytelling like that is about as close as I ever get to feeling like I’m home again. “You remember when,” we each began what must have been a dozen times. We shored each other up with all the nostalgia we could muster. Like family, we swapped stories that we both already knew but still enjoyed hearing. We spoke of loved ones gone too soon from the world and all their quirks and blessings. We reassured each other that all the things we’d learned from those now past were still just as true nowadays. We did our best impressions of voices too silent in these last few years. We even took a turn or two each at telling a story about ourselves that would be embarrassing in any context other than family.

I don’t need Max to be my dad – I had one of the best already and continue to benefit from his legacy and memory. Max doesn’t need me to be his son – he has found a home and family where God has planted him. But, somehow, Max and I still need each other. Perhaps we are brothers, united not by blood but by a curious mixture of fidelity and memory. It’s hard to say and I can’t imagine the specifics matter in the end, but I’ve learned my only answer from Max and all my other extended family: “he’s not my blood, but he’s my family.” It’s as good an answer as any other I can find.

***

Please consider making a donation to support our continued work at: bit.ly/3CMdonate.